The Rave

Hydrofoil

Redefining Fun, Speed

& Comfort

by Thom Burns

"A Boat That Flies"

I ordered the boat before it was in production after having sailed the

prototypes a couple of times in Florida. I took possession just before Labor Day, which in

this part of the world means I had about a month to sail it before being driven off the

lake by ol’ man winter. I’ve been holding off writing this review for awhile

because I wanted to confidently say what this boat really does. That confidence came

together when I attended the first national RAVE hydrofoil clinic held at Jensen Beach,

Florida in April.

I ordered the boat before it was in production after having sailed the

prototypes a couple of times in Florida. I took possession just before Labor Day, which in

this part of the world means I had about a month to sail it before being driven off the

lake by ol’ man winter. I’ve been holding off writing this review for awhile

because I wanted to confidently say what this boat really does. That confidence came

together when I attended the first national RAVE hydrofoil clinic held at Jensen Beach,

Florida in April.

The entire design team from Hydrosail, the one-design class

president and the Wilderness Systems

factory point man were there. Ten of us from the clinic, ranging from new buyers to

dealers, really learned this boat with most of its bells and whistles.

Background

Before diving into the particular characteristics of the Rave let’s review a couple of principles of boatspeed as

I understand them.

Before diving into the particular characteristics of the Rave let’s review a couple of principles of boatspeed as

I understand them.

Most sailboats, including my racing keelboat, bore holes in the water.

They are restricted to a top speed by the bow wave they are pushing and towing through the

water. This top speed, called hull speed, is usually defined by a formula. This formula is

about 1.2 times the square root of the waterline. If a boat has a twenty-five foot

waterline the top speed would be 1.2 X 5 = 6 knots. In order to go faster the boat must

temporarily increase its waterline or break out of its bow wave by planing over it.

Many keelboats with flatter bottoms, and boats such as scows and

planing trimarans, are capable of escaping the bow wave and planing. Once

on a plane a new speed restriction takes over. This is friction of the boat over the

wetted surface; water. The less the wetted surface, or, the more of the boat which is out

of the water, the faster the boat will go. This is why sportboats, planing multihulls and

even Whitbread 60’s are so fast compared to boats restricted to the bow

wave/waterline formula.

the bow wave and planing. Once

on a plane a new speed restriction takes over. This is friction of the boat over the

wetted surface; water. The less the wetted surface, or, the more of the boat which is out

of the water, the faster the boat will go. This is why sportboats, planing multihulls and

even Whitbread 60’s are so fast compared to boats restricted to the bow

wave/waterline formula.

The ultimate reduction in wetted surface area is to take the boat

completely out of the water. The Rave hydrofoil ultimately reduces wetted surface area to

about 22 to 23 square feet. This allows the sailplan to power up the boat to fly to some

new theoretical limits imposed by cavitation over the hydrofoil wings (bubbles over the

wings). The generally accepted maximum before meeting the cavitation barrier is about 42

knots. The recommended top speed of the Rave is 30 knots.

The complexity of the hydrofoil boat arises from the fact that it sails

under all the speed barriers at different times and is able to overcome all but cavitation

at different times. See the related article about the 42 NM Miami to Key Largo race which

included 10 Raves in their first offshore one design class.

The RAVE

The first thing that impressed me is how extraordinarily well the boat

performs as a sailboat when not on foils. It points 40 to 45 degrees to the apparent wind,

it tacks on a dime with a self-tacking jib and jibes with ease. You can feel everything

that this big powerful rig gives you.

Sailing Flat

Hydrofoil boats need to sail flat to give the wings the proper angle of

incidence in the water. Get used to not heeling. This translates into considerable

stresses since the sailplan is at its optimum when straight up and down. These stresses

are absorbed by the aluminum grid and large cross beam before they are transferred into

power and speed.

Upwind

You have to shake your preconceptions here because you have so much

control over your vertical foils which lift you to windward as well as your horizontal

foils which hoist the boat clear of the water.

In light winds (4 - 8 knots) you are in a displacement mode. The

windward foil is lowered all the way while maintaining your leeward foil at half latch and

your rudder foil at half latch. This configuration gives you a lot of lift to windward

with minimum drag. It is also one of the few times you’ll heel at all.

In a little more breeze, 9 to 14 knots, you can skim to windward. This

is done by taking advantage of the horizontal foils’ lifting power to minimize wetted

surface, thus increasing speed to windward. All foils are fully extended.

In yet more breeze, 15 plus knots, you can foil to windward. All foils

are fully extended, boat speed is between 14 and 18 knots at approximately 58 to 60

degrees to the apparent wind.

Since the windspeed fluctuates, you may not always be on foils upwind.

One efficient method of going upwind is, when you land in the lulls, to trim in and point

up to 45 degrees apparent wind. In the puffs fall off a bit and foil to windward at high

speed.

Beam Reaching

This is the fastest point of sail and the one which requires the least

amount of wind in order to come out of the water on foil. It is not uncommon to bring a

Rave up on foil in 8 to 9 knots of wind. As your skill increases you can do flying jibes.

This is when the G-forces remind you that its very nice to be captured in a seat.

Broad Reaching

The further downwind you go the slower the boat goes relative to the

windspeed and the less stress you put on the boat. In very high winds, if you come off

foil without pointing the boat into the wind, you are most vulnerable to nosing the boat

over. This is not a violent pitch pole such as in some high speed beach cats, but rather a

slow elevator ride to 90 degrees.

Company History

Wilderness Systems began in Andy Zimmerman’s garage in 1985. Andy

and his partner, John Sheppard, decided to build a few kayaks for their friends. They had

both recently left the furniture industry. Building whitewater kayaks seemed to be more

fun.

Despite the fact that the market appeared to be already saturated, it

turned out to be more than just fun, it became a great success. They found a niche in

building touring kayaks, an item which other companies were not very interested in at the

time.

The glitch in the production process was that their hand-made boats

were too expensive to produce. So, in 1991 they began the rotational molding process, and

applied it to their most popular touring kayak, the Sealution. The result was a high-level

performance kayak at almost half the price of the composite version!

The real explosion in sales came when the company, using its own

in-house research and development team, created a new line of kayaks for the masses which

were stable, inexpensive and easy to paddle. In 1993 the Rascal was born and became an

instant hit.

Through the years the company offered several versions of sailing

kayaks. When Andy and John teamed up with Jim Brown, creator of the SeaRunner 31 and 37,

the WindRider trimaran was created as a new product and WindRider Sailing Trimarans became

a new division within the company.

In 1996 the first roto-molded, wave-piercing trimaran left the factory,

followed by hundreds more. According to Andy, Wilderness Systems is building over 30,000

small boats a year.

Construction

The Rave, like WindRider, is roto molded polyethylene plastic. The raw

material is a powder which is poured into a mold then rotated and baked. After the baking

process, it takes 20 - 30 minutes for cooling to take place. Then assembly begins. Pieces

such as cut-outs and shavings are reground and reused. It is almost a "no waste"

process.

The difference between rotational molding manufacturers is primarily

how they use the process to build boats. Since polyethylene is a really tough, but

relatively soft, pliable material, it gains its structural strength by creating curves,

ridges, angles, pegs between layers, etc. The downside of this is that when there is

enough plastic in place to deal with the rig loads and hull stresses of sail boats, the

boat tends to get "heavy" and the continual flexing may degrade the stress

points anyway.

Andy and Wilderness Systems have taken a far superior approach by using

the roto molded polyethylene to keep the water out of the boat or to "float the

boat." The structural integrity, and tremendous stress loads of the RAVE hydrofoil

are taken by an aircraft aluminum tubing structure which is both simple and strong. Even

the foils are aluminum and they are supported by a large five inch aluminum crossbeam.

The Foil System

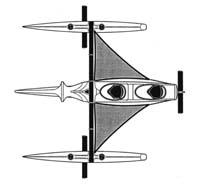

The crossbeam and tubing grid support three inverted

"T" shaped hydrofoils. The left and right foils have an automatic control arm

which adjusts the aileron flap on the back of the wing. This mechanical system controls

lift and drag to keep the boat flying evenly through the water at the right depth. Bungee

adjusting cords are manually controlled from the cockpit to assist and tune the automatic

system. All the foils have three positions: all the way up, all the way down and

half-latch. If the boat is moving the foils can be flown to the proper position either up

or down.

The crossbeam and tubing grid support three inverted

"T" shaped hydrofoils. The left and right foils have an automatic control arm

which adjusts the aileron flap on the back of the wing. This mechanical system controls

lift and drag to keep the boat flying evenly through the water at the right depth. Bungee

adjusting cords are manually controlled from the cockpit to assist and tune the automatic

system. All the foils have three positions: all the way up, all the way down and

half-latch. If the boat is moving the foils can be flown to the proper position either up

or down.

The stock rudder foil is a neutral, following wing. As the front foils

rise, the angle of incidence increases giving the rudder foil lift to raise the boat

completely out of the water. When the boat is foil borne the rudder foil returns to near

neutral.

The adjustable pitch rudder which I prefer has an aileron on the back

of the foil just like the side foils do. You control the lift and drag by moving a control

arm on the side of the cockpit. This can assist when becoming foilborne and in tuning the

boat when on foil.

The Rig

The large-roach, full-batten mainsail is boomless. After jibing a

couple of times at 20 plus knots, it’ll make sense. The jibe is over in a couple of

seconds and you are off on the other tack without ever leaving your foil "feet."

This is another time when warp speed is added to your sailing vocabulary.

The jib is small and self-tacking. It obviously works very well because

the boat tacks on a dime. It’s so much better than comparable sized beach catamarans

when tacking that it sets a new standard more akin to quick monohulls.

The roller-furling reacher adds 97 sq. ft. to the already impressive

193 sq. ft. sailplan. The reacher extends the wind range. It is easy to handle and powers

up the boat in lighter air. It also allows lower downwind angles when flying on foil. This

sail is usually referred to as the screecher by multihull enthusiasts.

The Rave has a rotating aluminum foil-shaped spar with upper and lower

shrouds but no backstay. It’s a relatively simple, cost-effective rig which performs

well.

The Designers

Dr. Sam Bradfield is a jewel of a person. His passion is sailing fast.

He spent eight years at the University of Minnesota in aeronautical engineering before

moving back to private industry and eventually to Florida. His expertise in fluid dynamics

and advanced wind powered watercraft eventually led to hydrofoils. He designed NF2,

Neither Fish Nor Fowl. Nf2 captured and held the Class C world speed sailing record

between 1978 and 1982.

Sam and his associates at HydroSail, Inc., Mike McGarry and Tom Haman,

set their sights on developing practical applications which could bring hydrofoil sailing

and racing to regular folks. They developed foils for wind surfers and retrofits for

catamarans. According to Mike, one of the problems with retrofits is that the original

boats were not designed to handle the additional loads required to sail flat with

hydrofoils. "It’s much easier to design the boat right from scratch."

Sam beamed when I told him that the factory just placed the 150th Rave

order since last August. "It has been a really great team effort between the factory

and the design team. It wouldn’t have happened without great sacrifice and

cooperation between both teams."

How Tough Is Tough?

A friend of mine got his Rave and immediately launched it in North Dakota. He

went out and sailed in 30 knot winds without a reef (recommended at 20 knots). He promptly

ran aground at a speed of 30 knots. The extent of the damage was a cracked weld where the

crossbeam bolts together.

A friend of mine got his Rave and immediately launched it in North Dakota. He

went out and sailed in 30 knot winds without a reef (recommended at 20 knots). He promptly

ran aground at a speed of 30 knots. The extent of the damage was a cracked weld where the

crossbeam bolts together.

Another Rave owner ran aground in shallow water in Florida going about

28 knots. He broke his foil on the coral. Replacement cost was under $400. Imagine any

other boat, power or sail, running aground at these speeds. The owners would be fortunate

if the boats weren’t total losses.

I pitched my Rave forward in a 30 plus knot gust by flying the leeward

foil out of water at very high speed. This caused the boat to turn dead downwind with all

of its sails up and no way to release the main past the shrouds. It was a slow elevator

ride up and neither I nor the boat suffered any damage. I'm an advocate of reefing and

paying attention to both foils now!

Conclusion

The WindRider Rave is a fun boat to sail in displacement mode.

It’s a fine sailboat with good speed and pointing ability. Its large square-topped main,

rotating mast, self-tacking jib, asymmetrical roller furling screecher package and, of

course, the foil system allow for plenty of growth for the experienced sailor while

novices can successfully "fly" it. Changing gears in a machine like this is

almost redefining the term.

main,

rotating mast, self-tacking jib, asymmetrical roller furling screecher package and, of

course, the foil system allow for plenty of growth for the experienced sailor while

novices can successfully "fly" it. Changing gears in a machine like this is

almost redefining the term.

Somehow, a scream or hoot escapes from even the most experienced

sailors when the craft first comes up on foil. The boat is completely out of the water and

you are moving along smoothly at 1.5 to 2.0 times windspeed. Pause for a moment and

remember what you’re doing on a conventional or sport boat when its topped out (white

knuckles - heeled and hiked to the max). On the Rave you’re comfortably sitting in

your seat "flying" your machine.

I get a special charge when powerboats and jet skis try to vector an

intercept course to figure out or clock the Rave. A big smile creeps onto my face as I

pass every high tech machine in sight often at two or three times their boat speed knowing

my checkbook took a minor hit and I didn’t have to coordinate a half dozen crew

members.

Possibly the strongest suit this boat has is the ability of a wide

range of folks from novice to very experienced to have fun, fly a modest speeds and doing

it all from the comfort of your own seat. If you’re looking for a well-designed,

innovative, fun, comfortable machine with a growing one design class which is really

comfortable for you and your passenger, the Rave may be it.

Thom Burns publishes Northern Breezes. He also reps WindRider

Trimarans in eight midwestern states.

For more info: Call 800-311-7245 or 763-542-9707.

About Sailing Breezes Magazine

Please send us your comments!!

All contents

are copyright (c) 1998

by Northern Breezes, Inc. All information contained within is deemed reliable but carries

no guarantees. Reproduction of any part or whole of this publication in any form by

mechanical or electronic means, including information retrieval is prohibited except by

consent of the publisher.

I ordered the boat before it was in production after having sailed the

prototypes a couple of times in Florida. I took possession just before Labor Day, which in

this part of the world means I had about a month to sail it before being driven off the

lake by ol’ man winter. I’ve been holding off writing this review for awhile

because I wanted to confidently say what this boat really does. That confidence came

together when I attended the first national RAVE hydrofoil clinic held at Jensen Beach,

Florida in April.

I ordered the boat before it was in production after having sailed the

prototypes a couple of times in Florida. I took possession just before Labor Day, which in

this part of the world means I had about a month to sail it before being driven off the

lake by ol’ man winter. I’ve been holding off writing this review for awhile

because I wanted to confidently say what this boat really does. That confidence came

together when I attended the first national RAVE hydrofoil clinic held at Jensen Beach,

Florida in April. Before diving into the particular characteristics of

Before diving into the particular characteristics of  the bow wave and planing. Once

on a plane a new speed restriction takes over. This is friction of the boat over the

wetted surface; water. The less the wetted surface, or, the more of the boat which is out

of the water, the faster the boat will go. This is why sportboats, planing multihulls and

even Whitbread 60’s are so fast compared to boats restricted to the bow

wave/waterline formula.

the bow wave and planing. Once

on a plane a new speed restriction takes over. This is friction of the boat over the

wetted surface; water. The less the wetted surface, or, the more of the boat which is out

of the water, the faster the boat will go. This is why sportboats, planing multihulls and

even Whitbread 60’s are so fast compared to boats restricted to the bow

wave/waterline formula. The crossbeam and tubing grid support three inverted

"T" shaped hydrofoils. The left and right foils have an automatic control arm

which adjusts the aileron flap on the back of the wing. This mechanical system controls

lift and drag to keep the boat flying evenly through the water at the right depth. Bungee

adjusting cords are manually controlled from the cockpit to assist and tune the automatic

system. All the foils have three positions: all the way up, all the way down and

half-latch. If the boat is moving the foils can be flown to the proper position either up

or down.

The crossbeam and tubing grid support three inverted

"T" shaped hydrofoils. The left and right foils have an automatic control arm

which adjusts the aileron flap on the back of the wing. This mechanical system controls

lift and drag to keep the boat flying evenly through the water at the right depth. Bungee

adjusting cords are manually controlled from the cockpit to assist and tune the automatic

system. All the foils have three positions: all the way up, all the way down and

half-latch. If the boat is moving the foils can be flown to the proper position either up

or down. A friend of mine got his Rave and immediately launched it in North Dakota. He

went out and sailed in 30 knot winds without a reef (recommended at 20 knots). He promptly

ran aground at a speed of 30 knots. The extent of the damage was a cracked weld where the

crossbeam bolts together.

A friend of mine got his Rave and immediately launched it in North Dakota. He

went out and sailed in 30 knot winds without a reef (recommended at 20 knots). He promptly

ran aground at a speed of 30 knots. The extent of the damage was a cracked weld where the

crossbeam bolts together. main,

rotating mast, self-tacking jib, asymmetrical roller furling screecher package and, of

course, the foil system allow for plenty of growth for the experienced sailor while

novices can successfully "fly" it. Changing gears in a machine like this is

almost redefining the term.

main,

rotating mast, self-tacking jib, asymmetrical roller furling screecher package and, of

course, the foil system allow for plenty of growth for the experienced sailor while

novices can successfully "fly" it. Changing gears in a machine like this is

almost redefining the term.