Ducking Another Boat Upwind

by David Dellenbaugh

When you’re on port tack and you’re “ducking” (passing behind) a starboard tacker, there is good news and bad news. The bad news is that you will end up at least a full boat length behind the other boat. The good news is that you’re very close to them, and when you converge again you will have the right of way on starboard tack!

|

If you want a good chance at passing the other boat, however, you must execute a perfect dip behind their transom. This requires skillful boathandling technique and good coordination among your crew. Here are some helpful rules of thumb for the starboard tacker and the port tacker.

Both boats

Keep a good lookout. When you are sailing in traffic, especially in a strong breeze, watch out for boats around you. It’s obvious that a boat on port tack must look around because she has to keep clear of all starboard tackers. At the same time, a boat on starboard tack should also keep a good lookout because other boats will affect her tactics and, if they don’t see her, she is required to avoid contact.

Follow your strategy. Before you converge with another boat, think about your strategy. Which way do you want to be going after you encounter the other boat, and how can you best accomplish that? Ducking the other boat may or may not be a good idea.

Keep sailing fast. It’s easy to get distracted when you are close to other boats, but this usually makes you go slow. So try to stay focused. Keep your boat going fast so a) you won’t lose to the rest of the fleet; and b) the next time you converge with this boat you will have gained enough to cross clear ahead.

The starboard tacker

Yell “Starboard!” The rules don’t require you to say anything, but this is a sportsmanlike thing to do, plus it’s in your interest to make sure that P keeps clear of you.

Don’t change course. When two boats on opposite tacks are crossing on a beat, rule 16 places very strict limits on course changes by the starboard tacker. It’s OK for S to change her course when she is still a few lengths away from P, but after this she should steer straight until P has crossed clear astern (unless, of course, S must change course to avoid contact).

Keep watching P. In most ducking situations, S depends on P to bear off and avoid contact. Since this makes S a sitting duck, someone in her crew should keep an eye on P in case there is any problem.

The Port tacker

Watch the starboard tacker. One of the biggest problems in crossing situations is that the crew of P simply doesn’t see S approaching. This is especially true when it’s windy (and the boat is heeled over, which reduces visibility) or when your boat has an overlapping genoa. In these and all other cases, you must make sure someone is keeping a good lookout to leeward and ahead.

This could be the jib trimmer (if he or she is sitting to leeward), the mainsail trimmer (if he or she can see underneath the boom), the tactician (since he or she is in the back of the boat with a good view around the headsail leech) or the helmsperson (if he or she can see through the mainsail window or under the boom). In most cases, a good duck begins with plenty of warning - a last-minute scramble seldom works well.

Ease the mainsheet. The most important thing you must do when ducking another boat is to ease your mainsheet. This allows you to get proper mainsail trim as you reach off behind the other boat. It also keeps your boat from heeling over too far and thereby reduces windward helm.

If you fail to ease the sheet far enough, the boat will tend to round up instead of bear off. This is slow and potentially dangerous, so make sure your mainsail trimmer knows you will be ducking and is ready to ease the sheet quickly. Of course, if you have running backstays, the leeward runner must be loose or it will restrict the mainsail and make it difficult to bear off.

Don’t forget to ease your jib or genoa when you duck, too. This is good for speed and, in a breeze, may also be necessary to keep the boat from heeling too much.

Hike out hard. When you want to bear off, there are three ways to help turn your boat. You can use the rudder, which is slow. You can use the sails as we just described. And you can use your crew weight.

In the photo on the previous page, the crew of the port tacker should be max hiking as hard as possible. While they won’t be able to keep this boat flat, they will reduce leeward heel at least a little. That will help the boat turn with less rudder drag and make it easier for the skipper to bear off.

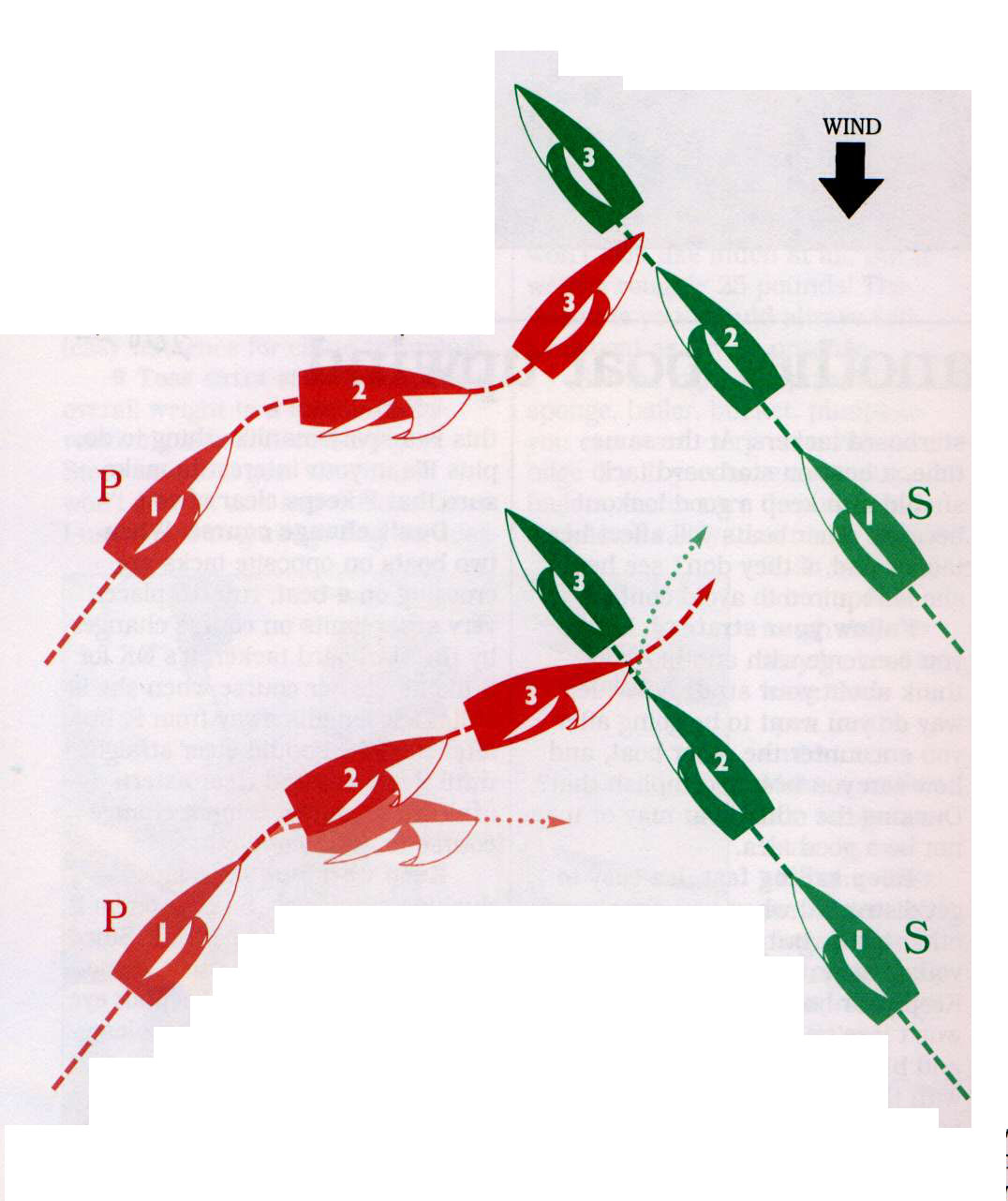

Make a good duck. You should normally bear off early and then start heading up so that when your bow reaches the stern of the other boat, you are back to a closehauled course (with a little extra speed). Unless there are other factors, this is the best way to minimize loss (see diagram - the Ideal Duck).

Sometimes, however, you may be worried that S will tack on you. This is often the case just after the start, for example, when everyone is looking for a lane. If you do an “ideal duck,” S will be able to tack while you are aiming behind her transom, and you’ll be in bad air.

To prevent this, aim at the middle of S while you are ducking (see diagram - the Defensive Duck). This way S won’t be able to tack because she would be changing course too close. At the last moment (or as soon as you’re sure S won’t tack), bear off and go behind S.

Another thing you can do to keep S from tacking is to yell “Hold your course” as you approach her. While this hail has no legal standing, it warns S that if she tacks she will risk breaking rule 16. Often it causes her to hesitiate long enough for you to get by her stern.

|

The Ideal Duck When ducking another boat (S), the most important thing is to be on a closehauled course, with speed, when your bow reaches S’s stern (position 3). To do this, start to bear off early (2) and then begin heading up as you converge more closely with S. Aim for a spot just behind the corner of S’s transom. Turn smoothly using crew weight and sail trim to maintain speed. Pass as close as you can in the existing conditions (without risking contact), so you lose as little distance as possible. |

| The Defensive Duck If you make a classic duck as described above, you give S the chance to tack right in front of you. That’s because when you bear off at position 2, S can tack and still keep clear of you. This is not good when you want to keep going on port tack. To prevent this, change the way you duck. Instead of aiming for S’s transom corner, bear off only far enough so you aim for her midships. This essentially “freezes” her course and prevents her from tacking. As you get closer, bear off just enough to pass behind S and then head up to closehauled. Since you pass S on a close reach, you will lose more distance than in the classic duck above. However, you gain the ability to keep sailing on port tack, Which could be much more valuable. |

Dave is a two-time America’s Cup veteran who publishes the newsletter Speed & Smarts. For a subscription call: 800-356-2200.